What are cilia?

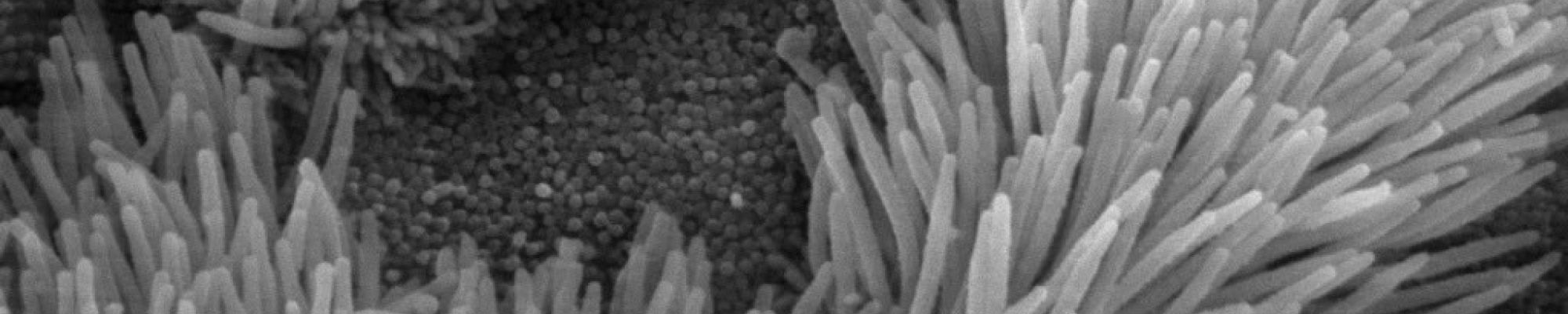

Cilia are slender, microscopic, hair-like structures or organelles that extend from the surface of nearly all mammalian cells. They are primordial.

What are cilia?

Cilia are slender, microscopic, hair-like structures or organelles that extend from the surface of nearly all mammalian cells. They are primordial.

Cilia

The ciliary system is connected to cell cycle progression and proliferation. Cilia play a vital part in human and animal development and in everyday life.

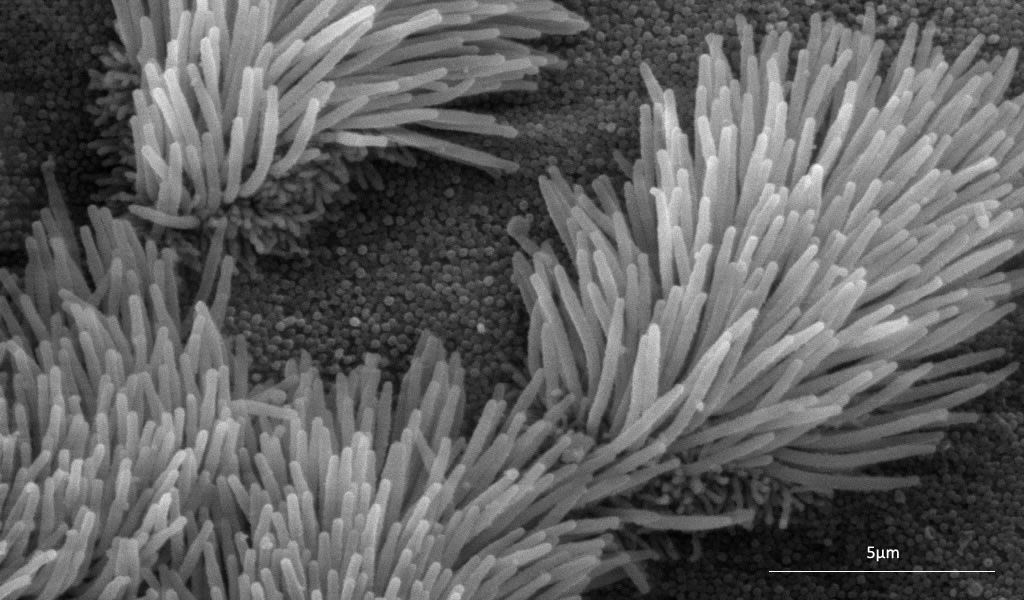

The length of a single cilium is typically 1-10 micrometres and width is less than 1 micrometre.

Cilia are broadly divided into two types. They function separately and sometimes together:

Motile (or moving) cilia are found as 200-300 cilia per cells in the airways (lungs, respiratory tract and middle ear), the brain ventricles and fallopian tube and are highly structurally related to sperm tails. These cilia have a rhythmic waving or beating motion moving forward and back. They work, for instance, to keep the airways clear of mucus and dirt, allowing us to breathe easily and without irritation. They also help propel sperm and eggs for fertility. During development, ‘nodal’ cilia that move in a circular pattern are involved in determining the left-right organisation of our internal organs.

Non-motile (also known as primary) cilia are found on almost all human cells. They typically appear as a single cilium on the cell. Our current understanding is that their role is primarily sensory, and in co-ordinating cell signalling pathways.

In the kidney, for example, the primary cilia bend with urine flow and send a signal to alert the cells that there is a flow of urine.

In the eye, non-motile ‘connecting’ cilia are found inside the light-sensitive cells (photoreceptors) of the retina. These cilia act like microscopic train-tracks, that allow the transport of vital molecules from one end of the photoreceptor to the other.

Structure and Function of Cilia

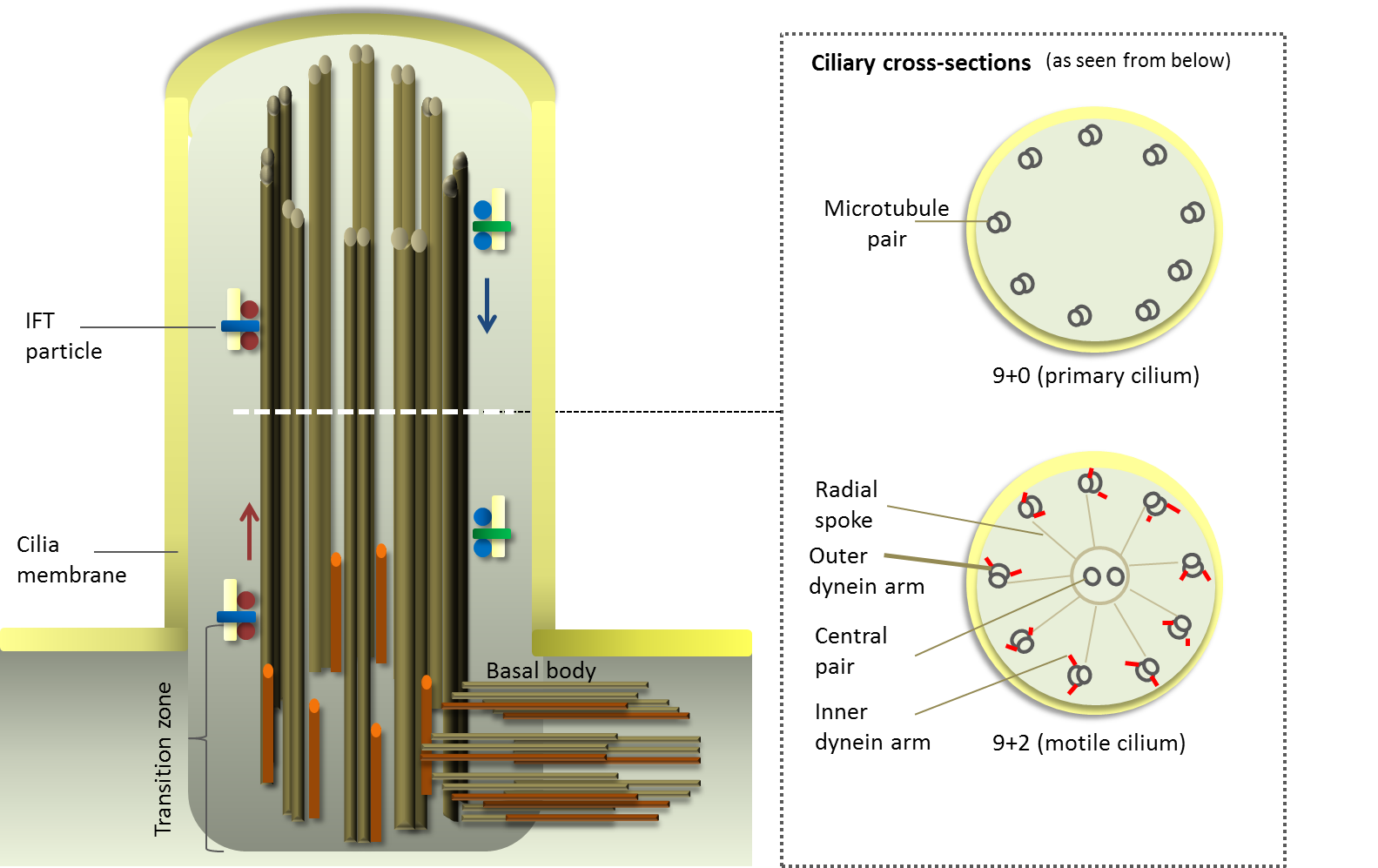

Structurally, each cilium comprises a microtubular backbone - the ciliary axoneme - surrounded by plasma membrane (see figure below).

Motile cilia are characterized by a typical ’9+2’ architecture with nine outer microtubule doublets and a central pair of microtubules, present as multiple motile cilia on the cell surface (e.g in bronchi of the lungs).

Non-motile (primary) cilia with a typical ‘9+0’ architecture appear typically as single appendage microtubules on the apical surface of cells and lack the central pair of microtubules (e.g. in kidney tubules).

Ciliary proteins are synthesized in the cell body then imported into the cilia and they must be transported to the tip of the axoneme. This is achieved by intraflagellar transport (IFT), an ordered and highly regulated anterograde (base to tip) and retrograde (tip to base) involving translocation of protein complexes (IFT particles) that carry cargo along the length of the ciliary axoneme.

Dysfunction or defects in motile and non-motile cilia underlie an expanding number of devastating genetic conditions - termed ciliopathies - which form an important category of diseases that carry a heavy health and economic burden on individuals, families and society.

Much is still unknown about the structure and function of motile and non-motile cilia, but we believe that more research into these critically important cellular organelles will eventually bring about better ways to treat and help people whose lives are impacted by defective cilia.

Impact of Defective Cilia

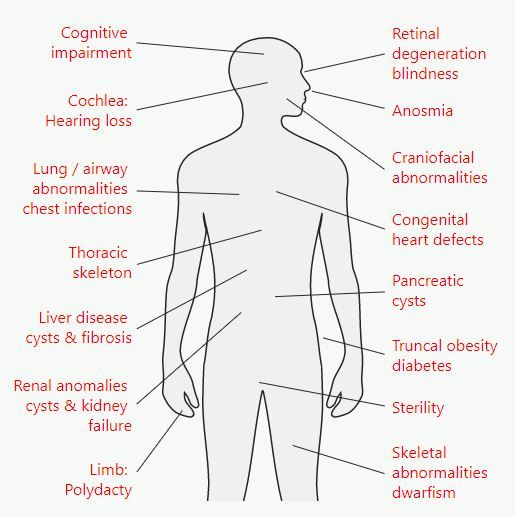

Defective and dysfunctional functioning in motile and non-motile cilia results in cilia motility and signalling defects that cause a large number of symptoms and disorders, which have significant impact on those affected.

As cilia are found on most cell types, defective cilia may affect multiple systems in the body, causing blindness, deafness, chronic respiratory infections, kidney disease, heart disease, infertility, obesity and diabetes. These symptoms have significant impact on those affected; some are devastating, most are life-threatening.

The diagram indicates the effects and a non-exhaustive summary of some of these symptoms is provided below. For information on known and identified ciliopathy syndromes and diseases, see Ciliopathies.

Lung / airway abnormalities

Motile cilia line the respiratory airways, to help clear mucus and dust. As well as primary ciliary dyskinesia, sinusitis, rhinitis, bronchitis and otitis have all been associated with motile cilia dysfunction.

Renal anomalies, eg cystic kidneys

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD) and nephronophthisis (NPHP) are the major inherited cystic kidney diseases.

The cilia in the epithelial cells in the kidney point into the urine and sense the flow. This stops cells dividing and send a signal to control urine concentration. When the cilia are defective, there is no signal and too much cell division, resulting in uncontrolled cyst formation..

Retinal degeneration, rod cone dystrophy and retinitis pigmentosa

Cilia are found inside photoreceptors in the eyes. They connect the inner segment to the outer segment and carry proteins made in the inner segment to outer segment. Malfunction stops transport of vital proteins, and the photoreceptors die.

Anosmia

Airway congestion, glue ear, hearing loss.

Congenital heart defects

Cilia are important during development of the heart. Flow of fluid is sensed by cilia leading to changes of cell growth. Failure of cilia leads to left left-right asymmetry, eg situs inversus.